Why "ChatGPT for Your Data" Keeps Failing in Production

What we learned building real-time intelligence for PE deal teams.

You're on a call with a company's CFO. They mention revenue grew 15% last year. But your system flags a conflict: the earnings report you indexed last week showed 20% growth. Either the CFO misspoke, the report had a typo, or you're comparing different metrics.

You have about 10 seconds before the pause gets awkward.

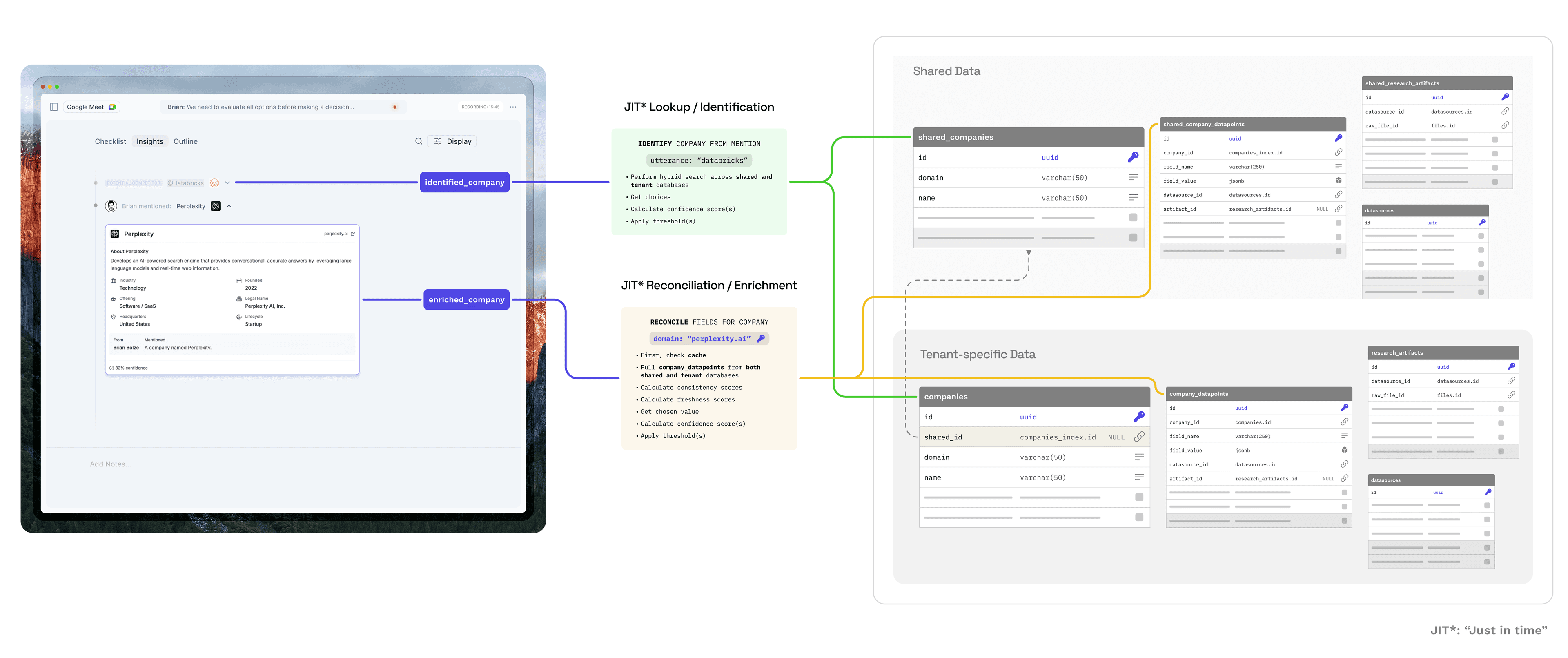

This was one of our design constraints at Doro: provide intelligence to PE analysts during live conversations. Not just answers to questions—automatic cross-referencing against everything we knew about the company, surfaced in real-time. Sub-200ms latency. Complete source attribution so analysts could trust the flag. Field-level privacy so public data could blend with confidential expert calls without crossing tenant boundaries.

We spent 12 months learning that the hard part of "AI for your data" isn't the AI. It's the data architecture.

This post explains the architecture we built, why vector RAG wasn't enough, and when you actually need this level of complexity.

The Problem: Entity-Centric Intelligence at Scale

The scenario above—contradiction detection during a live call—requires structured knowledge about entities: companies, people, deals, products. Each has attributes you want to query, filter, compare, and audit. When the CFO mentions a number, you need to cross-reference it instantly against everything you already know.

This pattern has a name—entity-centric knowledge—and it's much older than this AI hype cycle. Google's Knowledge Graph powers those info boxes when you search for "Apple" or "Eiffel Tower." CRMs like Salesforce organize companies, contacts, and opportunities with attributes you can filter and aggregate. The pattern exists. Building one for your data has historically been too complex for most teams.

Why This Has Been So Hard

Entity-centric knowledge systems are notoriously difficult to get right. Extraction meant custom NER models, annotation teams, and ML infrastructure. Entity resolution required hand-tuned heuristics that broke on edge cases. Classification—is this company B2B or B2C? What's their primary industry?—meant training domain-specific models for every taxonomy. The challenges compound: get any piece wrong and the whole system becomes unreliable. Building a trustworthy knowledge graph used to require Google-scale resources.

So most organizations don't build. They buy.

Early in our customer discovery, a partner at a top Private Equity firm told us something striking: they paid for all the major market data platforms—Pitchbook, CB Insights, AlphaSense—but considered them "essentially useless" because they didn't trust the data. Millions per year on data they can't rely on for high-stakes decisions.

The firms we talked to weren't lacking data—they were lacking trust.

The problem wasn't data availability. It was provenance and reconciliation. When Pitchbook says 150 employees and Crunchbase says 200, which is right? When did each source last update? Can you trace the claim to an actual observation? For decisions involving millions of dollars, "the database said so" isn't good enough.

Analysts at these firms were already pulling from multiple sources and reconciling manually—but not systematically. They'd pay expert networks to conduct the same research repeatedly, often talking to the same experts, because insights from previous calls weren't captured in any reusable form. The institutional knowledge just leaked away.

Modern AI changes the economics of building systems that actually earn that trust.

Extraction that required custom models now works with off-the-shelf LLMs and careful prompting. We could pull structured facts from transcripts, PDFs, and websites without training anything.

Entity resolution that needed brittle heuristics can leverage embeddings for fuzzy matching and LLM judgment for ambiguous cases. "Is this the same company?" becomes tractable.

On-the-fly classification was the underrated unlock. Say you want to tag companies by "primary industry" using categories you define: "Enterprise SaaS," "Consumer Hardware," "Fintech." Previously? Annotation, labeled data, ML pipeline. Now? Generate embeddings for your category descriptions, embed the company's source text, pick the closest match. No training data, no model pipeline, works with user-defined taxonomies that you can change tomorrow.

This last insight shaped our architecture more than anything else. If you can classify and normalize at ingestion time rather than query time, you can store structured, filterable data instead of hoping an LLM infers your categories consistently every time you ask. That's the difference between a queryable database and a pile of vectors you search through.

AI doesn't eliminate the need for data architecture. It makes building that architecture economically viable for a 2-person team. But "viable" isn't "automatic"—especially when production requirements enter the picture.

The Requirements That Killed Our First Three Ideas

A researcher at one of the Big 3 management consulting firms told us they'd buy our product if all it did was "bullshit detection" for expert calls. Apparently it's common to pay for research calls only to discover the "expert" has no idea what they're talking about. But here's the harder question: what if you discover an expert was unreliable after you've already extracted insights from their calls?

You need to retroactively adjust confidence in everything that expert said—without corrupting your data or losing the audit trail. That's not a feature you bolt on. It's a property of how you store facts in the first place.

Our real-time use case added another constraint. Live transcription delivers text in chunks—typically every 1-5 words to minimize latency. A 60-minute meeting means 2,000-10,000 chunks to process. When we calculated this, it killed most of our initial ideas: LLMs cannot be in the critical path. At $0.01+ per call, that's $20-100 per meeting just for entity lookups—plus 2-3 second latency per chunk.

After killing several approaches, four requirements emerged as non-negotiable:

Complete provenance with retroactive adjustment: Every fact traces to its source—which document, which extraction strategy, when observed. When a source is later discredited, you systematically downweight everything derived from it.

Field-level privacy: Blending public data with confidential sources requires granular access control. Same entity, different field visibility based on where each fact originated.

Sub-200ms queries: Real-time means no LLMs in the query path. At thousands of queries per day, costs must stay under $0.01 each.

Deterministic reconciliation: When the system flags a contradiction, it must explain why. Same query, same answer—every time.

These requirements aren't unique to PE diligence. They apply to any entity-centric system where decisions have consequences: healthcare organizations reconciling patient records, legal teams tracking entities across filings, financial services blending market data with proprietary research. We built for deal teams, but the patterns generalize.

The requirements pointed toward a counterintuitive design decision: don't store entity state at all. Store immutable facts—datapoints—and compute entity state on demand. This is event sourcing applied to knowledge, and it's the foundation everything else builds on. More on that after we see why simpler approaches fail.

Why Query-Time AI Falls Short

Vector RAG is most teams' default for "AI on your data." Chunk documents, embed them, retrieve similar passages, feed to an LLM. It works beautifully for semantic search—"find documents about X."

It fails for structured queries about entities.

Consider: "How many companies in our database have 100-500 employees?"

Vector RAG retrieves the top-k chunks most semantically similar to your query—maybe 10, maybe 50. But your database might contain employee counts for 3,000 companies scattered across thousands of chunks. You're searching by similarity when you need exhaustive retrieval. The LLM can only count what it sees, and it's seeing a sample, not the complete picture.

Worse, there's no guarantee the right chunks even surface. A passage stating "Acme Corp's headcount grew to 150 last quarter" is about employee counts, but it may not be semantically similar to "companies with 100-500 employees." Vector search finds passages that sound like your question, not passages that answer it.

The real distinction isn't which database you use—it's when AI processing happens.

| Vector RAG | Datapoint Architecture | |

|---|---|---|

| When AI runs | Query time | Ingestion time |

| Core model | Retrieve chunks, reason on demand | Extract & structure upfront, filter on demand |

| Best for | "Find passages about X" | "All companies where revenue > $10M" |

| Provenance | Document-level | Field-level (immutable) |

| Reconciliation | Hope the LLM figures it out | Systematic, configurable |

| Query latency | 2-5s (LLM in path) | <200ms (pre-computed) |

| Cost per query | $0.01-0.10 | ~$0.001 |

Vector RAG defers everything to query time: retrieve chunks, call an LLM, hope it figures out classification and synthesis on the fly. Every query pays the full cost of AI reasoning. "Hybrid" approaches that bolt a vector store onto a relational database don't change this—if embeddings and LLM calls are required for every query, you inherit the latency, cost, and non-determinism.

Our Datapoint Architecture inverts this. Extraction, entity resolution, classification, normalization—all happen at ingestion time, when you can afford the latency and cost. By the time a query arrives, the hard work is done. You're filtering pre-computed, pre-classified structured data. Embeddings are used extensively—for entity resolution, for classification, for some queries—but they're tools for ingestion, not dependencies for every lookup.

AI doesn't mean you can skip structuring your data—it means you can finally structure data that used to be too messy to model.

The trap is thinking you can embed everything and let LLMs figure it out at query time. That works for demos. It fails when you need speed, determinism, or audit trails. The unlock is using AI at ingestion—extraction, classification, normalization—to populate rigorous schemas from sources that previously couldn't feed structured databases at all.

This is the trade-off: more upfront work, and you need to know your schema before you ingest. But queries become fast, cheap, and deterministic—and mistakes become traceable rather than invisible.

The Architecture

Our architecture inverts how most systems store entity data. Instead of mutable records that get updated when new information arrives, we store immutable observations—datapoints—and compute current entity state on demand.

This is event sourcing applied to knowledge. And it's what makes provenance, reconciliation, and retroactive correction architecturally possible rather than bolted-on afterthoughts.

Datapoints: The Core Abstraction

A traditional database might have a companies table with an employee_count column. When you learn a new number, you update the row. The old value is gone. If someone asks "where did this number come from?" you're checking logs, if you kept them.

We inverted this. Instead of mutable entity records, we store immutable datapoints—individual observations that never change once written.

@dataclass

class CompanyDatapoint:

id: UUID

company_id: UUID

field_name: str # "employee_count", "revenue", "industry"

field_value: Any # The actual value

confidence_score: float # 0-1, how much we trust this

# Provenance (where this came from)

research_artifact_id: UUID # The source document

extraction_strategy: str # How we extracted it

created_time: datetime # When we observed it

# Optional context

context_snippet: str # Surrounding text for audit

A company's "employee count" isn't a field on the company—it's a query that reconciles all employee_count datapoints for that company and picks the best answer.

The pattern applies to any entity type. We're showing company_datapoints here, but the same abstraction works for people, products, deals, markets. Different fields, same architecture.

Why does immutability matter? Because it preserves optionality. You never lose information. When you need to answer "what did we know last quarter?" or "which sources support this claim?" or "what changes if we stop trusting this expert?"—the answers are in the data, not in your memory of what you deleted.

With that foundation in place, here's what happens when data enters our system.

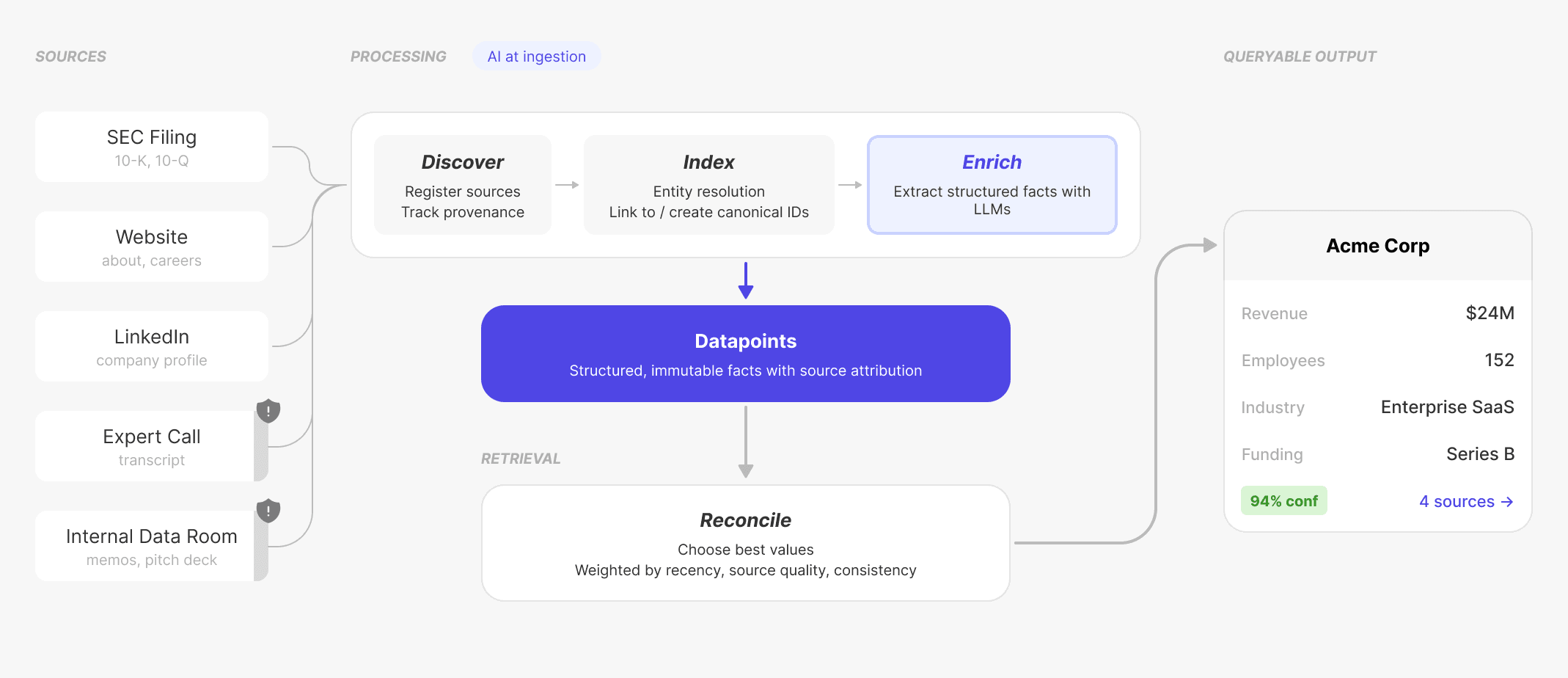

Data Flow Overview

A transcript from an expert call arrives. By the time it's queryable, we've already identified which entities are mentioned, resolved them to canonical records, extracted structured facts, scored confidence, and normalized values into filterable categories. The query just filters rows.

Let's walk through each stage.

Stage 1: Discovery

Discovery registers sources—transcripts, PDFs, earnings reports, LinkedIn profiles—and queues these “research artifacts” for processing. Each source gets a unique identifier that follows it through the pipeline. We're not extracting yet; we're establishing provenance.

Stage 2: Indexing

Indexing answers the question: what entities does this source talk about?

This is where entity resolution happens. When a transcript mentions "Google," we need to determine: is this Alphabet Inc.? A different company with Google in the name? The verb? And if it's Alphabet, we need to link this mention to our canonical record for that company.

We use a tiered approach, from cheap to expensive:

Exact matching catches obvious cases—fast, free, high confidence.

Fuzzy matching handles variations. "Acme Corporation," "ACME," "Acme Inc."—these should resolve to the same entity. We used token-based similarity (RapidFuzz) to catch these without hitting any APIs.

Embedding similarity comes next for harder cases. If the text says "the Mountain View search giant," there's no string match to find. But the embedding of that phrase lands close to our embedding of "Google/Alphabet" in vector space. We'd generate embeddings for ambiguous mentions and compare against our entity library.

LLM judgment is the last resort for genuinely ambiguous cases. Is "Apple" the company or the fruit? Usually context makes this obvious, but sometimes you need a model to read the surrounding sentences. We'd batch these calls to manage costs—they're expensive, but rare.

The output of indexing is a set of entity links: this source mentions these specific canonical entities. Now we can extract facts.

Stage 3: Enrichment

Enrichment is where unstructured sources become queryable data. Two things happen: extraction (pulling out specific facts) and normalization (mapping those facts to your schema). Extraction gets the attention, but normalization is the underrated unlock.

Extraction turns prose into structured claims. Consider a transcript where the CFO says: "We hit 150 employees last quarter, up from 120." That's two potential datapoints: employee count of 150 (current), and 120 (previous quarter). Each gets extracted with its context, timestamp, and source reference.

Extraction strategies vary by source type. For employee counts:

- Parse structured data from a paid API (high confidence)

- Extract from earnings reports using an LLM (medium-high confidence)

- Pull from conversational transcripts (medium confidence, requires context)

Each strategy has different reliability characteristics. We learned to encode these explicitly—a number from an SEC filing gets higher base confidence than one mentioned offhand in a call.

Normalization maps extracted values to your schema—and this is where embedding-based classification happens. Say you want to tag companies by industry using your own taxonomy: "Enterprise SaaS," "Consumer Hardware," "Fintech." A company's website talks about "B2B subscription software for sales teams." How do you tag it?

With embeddings, classification happens at ingestion with zero training data:

- Generate embeddings for each category in your taxonomy

- Embed text from the company's sources (website, descriptions, etc.)

- Pick the category with highest semantic similarity

"B2B subscription software for sales teams" lands near your "Enterprise SaaS" embedding even though those exact words don't appear in your taxonomy. The classification is semantic, not keyword-based—and it happens once, at ingestion, not on every query.

By the end of enrichment, we have a collection of datapoints: immutable facts, each traced to its source, each scored for confidence, each normalized into queryable fields.

Stage 4: Retrieval & Reconciliation

Here's where all that upfront work pays off.

When a query arrives, we're not calling an LLM or retrieving chunks. We're filtering structured data. "Companies with 100-500 employees in Enterprise SaaS" becomes SQL. Fast, deterministic, complete.

But there's a complication: what if we have three different employee counts for the same company?

Reconciliation chooses the best value when datapoints conflict. Our algorithm weighted several factors:

Source quality: SEC filings beat LinkedIn profiles beat passing mentions in transcripts. We maintained explicit rankings.

Freshness: A datapoint from last week beats one from six months ago—but with decay curves, not hard cutoffs. Recent data matters more, but old authoritative sources aren't worthless.

Consistency: If three sources agree and one disagrees, the outlier gets downweighted. But we flag the conflict rather than hiding it.

Field-specific rules: Some fields are exact (legal name) while others are approximate (revenue). Employee counts can reasonably vary by 10% between sources; if they vary by 50%, something's wrong.

The output is a reconciled value plus a confidence score plus links to all supporting datapoints. When the system tells you "150 employees (high confidence)," you can click through to see: LinkedIn said 148, the earnings report said 152, the expert call said "about 150." You can see why the system chose that number.

Here's the actual reconciliation logic (simplified):

View code snippet

def reconcile_datapoints(

datapoints: List[DataPoint],

config: ReconciliationConfig

) -> ReconciledValue:

"""

Choose best value from conflicting sources using:

- Source quality (LinkedIn > company website)

- Freshness (yesterday > 18 months ago)

- Consistency (do other sources agree?)

"""

# 1. Calculate freshness scores (exponential decay)

freshness_scores = [

exp(-age_in_days / decay_rate)

for dp in datapoints

]

# 2. Build consistency matrix (pairwise similarity)

consistency_matrix = [

[similarity(dp1.value, dp2.value) for dp2 in datapoints]

for dp1 in datapoints

]

# 3. Calculate weighted scores

scores = []

for i, dp in enumerate(datapoints):

score = (

dp.source.quality * config.weights.source_quality +

freshness_scores[i] * config.weights.freshness +

avg(consistency_matrix[i]) * config.weights.consistency

)

scores.append(score)

# 4. Choose highest-scoring value

best_idx = argmax(scores)

chosen_value = datapoints[best_idx].value

# 5. Find supporting/conflicting datapoints

supporting = [i for i in range(len(datapoints))

if consistency_matrix[best_idx][i] > threshold]

# 6. Calculate final confidence

confidence = calculate_confidence(

datapoints, supporting, consistency_matrix, freshness_scores

)

return ReconciledValue(

value=chosen_value,

confidence=confidence,

supporting_sources=[datapoints[i].source for i in supporting],

conflicting_sources=[datapoints[i].source for i in range(len(datapoints))

if i not in supporting]

)

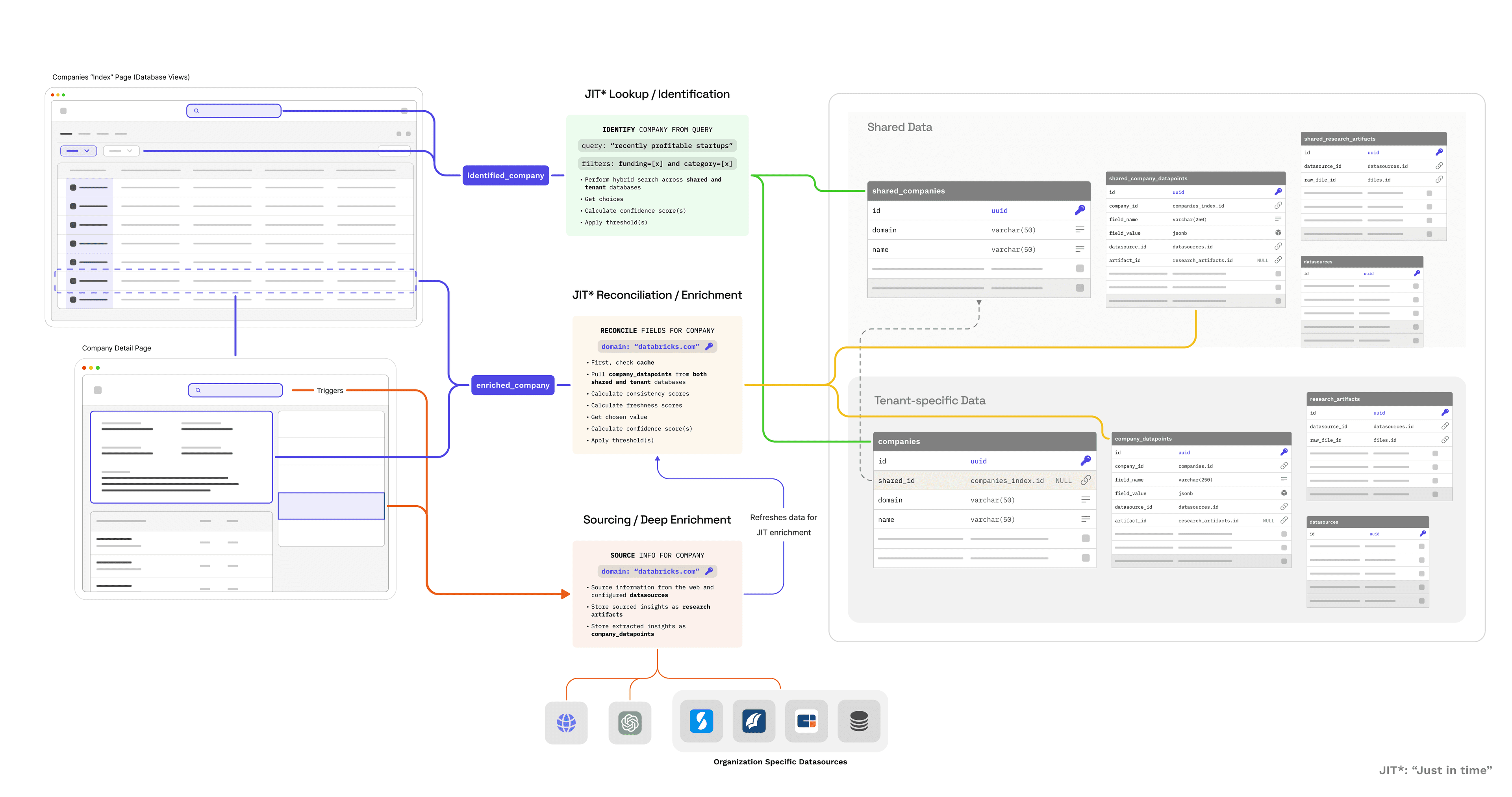

Performance tiers reflect different use cases:

Cached queries hit pre-computed reconciled values. When nothing has changed, this is a single database lookup. <50ms.

Reconciled queries recompute values when new datapoints have arrived. We'd run the reconciliation algorithm, update the cache, return the result. ~500-2000ms depending on conflict complexity.

Source new data queries trigger fresh extraction—useful for real-time use cases where you need the latest information. Seconds to minutes depending on sources involved.

For our live-call use case, we'd pre-warm caches for entities likely to come up in scheduled meetings. When the CFO mentioned their employee count, we weren't computing anything—just surfacing the pre-reconciled value and flagging the discrepancy we'd already detected.

What This Architecture Enables

Three capabilities fall out of this design that would be difficult or impossible to bolt on afterward.

Complete Provenance

Every field value traces to its sources—not as metadata attached to an entity, but as the actual structure of the data.

View code snippet

-- Full audit trail for any field

SELECT

dp.field_value,

dp.confidence_score,

dp.created_time,

ds.name as datasource,

ds.quality_score,

ra.metadata->>'url' as source_url

FROM company_datapoints dp

JOIN research_artifacts ra ON dp.research_artifact_id = ra.id

JOIN datasources ds ON ra.datasource_id = ds.id

WHERE dp.company_id = 'acme-corp-uuid'

AND dp.field_name = 'employee_count'

ORDER BY dp.created_time DESC;

| field_value | confidence | created_time | datasource | quality | source_url |

|-------------|------------|---------------------|------------|---------|----------------------|

| "127" | 0.95 | 2024-11-01 15:00:00 | Expert CFO | 0.95 | internal_call_123 |

| "100-150" | 0.85 | 2024-10-01 10:00:00 | LinkedIn | 0.85 | linkedin.com/acme |

| "100-150" | 0.75 | 2024-09-15 14:30:00 | Crunchbase | 0.75 | crunchbase.com/acme |

| "50+" | 0.40 | 2023-01-01 08:00:00 | Website | 0.40 | acme.com/about |

When reconciliation picks "127 employees" as the current value, you can see exactly why: the CFO said it last week, it's consistent with LinkedIn's range, and it supersedes the outdated website copy. The reasoning isn't hidden in an LLM's context window—it's in the data.

This matters when stakes are high. An analyst preparing a $50M investment memo can click any number and see its lineage. Auditors can verify claims. And when a source is later discredited, you can trace exactly what needs to be reevaluated.

Public-Private Data Blending

PE firms need to combine public market data with confidential insights from expert calls and data rooms. These can't leak between teams or tenants. But analysts want a single view that reconciles everything.

Our schema handles this with explicit separation:

public schema:

├── shared_companies

├── shared_company_datapoints ← LinkedIn, Crunchbase, SEC filings

└── shared_research_artifacts

tenant_acme schema:

├── companies ← Tenant-specific entity records

├── company_datapoints ← Expert calls, internal research

└── research_artifacts (linked to shared_companies via FK)

tenant_globex schema:

├── companies ← Completely isolated from Acme

├── company_datapoints

└── research_artifacts

At query time, reconciliation pulls from both pools, and the same reconciliation logic applies to all datapoints regardless of origin. Public sources establish a baseline; private sources can confirm, update, or override. An expert call saying "actually they have 200 employees now" beats last month's LinkedIn scrape—but both remain in the audit trail.

Crucially, Tenant A never sees Tenant B's private datapoints. The blending is per-tenant, and the public/private boundary is enforced at the schema level, not application logic.

Query-Time Performance

Because reconciliation produces structured, cached values, queries don't touch LLMs at all.

This enables UI patterns that would be prohibitively slow or expensive with vector RAG:

Live call integration: The use case we opened with. When the CFO mentions a number, we can surface contradictions immediately because we're querying pre-computed values, not reasoning about chunks in real-time.

Index views: Sortable, filterable tables across thousands of entities. "Show me Series B SaaS companies with 100-500 employees, sorted by revenue." That's a SQL query returning in 50ms. The "SaaS" filter isn't interpreted by an LLM—it's a field we populated when we first processed each company's sources. Change your taxonomy tomorrow, reprocess, and the new classifications are just as queryable.

Detail pages: Click into a company and see all its attributes instantly. No loading spinner while an LLM synthesizes information.

The economics matter too. Vector RAG at query time means every lookup costs $0.01-0.10 in LLM calls. At thousands of queries per day, that's $300-3,000/month just for reads. Our approach: LLM costs are at ingestion time only. Queries are effectively free.

But there's an obvious question we haven't addressed yet.

Building Reliable Systems with Unreliable AI

Here's the obvious objection: your whole system depends on LLMs extracting accurate data. LLMs hallucinate. Garbage in, garbage out.

Yes, extraction is imperfect. Here's what we actually measured:

| Source Type | Datapoint Extraction Accuracy |

|---|---|

| Structured APIs (LinkedIn, SEC) | 90%+ |

| Semi-structured (PDFs, slides) | 75-85% |

| Transcripts (expert calls) | 60-75% without review |

Those transcript numbers look scary. But the architecture handles this in ways that naive approaches can't.

Source provenance enables surgical cleanup. When you discover an expert was unreliable—or an extraction prompt had a bug—you can trace every datapoint that came from that source. Not "search for things that might be affected," but a precise query: "all datapoints from artifact X" or "all datapoints extracted with strategy Y before version Z."

From there, you have options. Delete the datapoints. Lower their confidence scores. Reprocess with a better extraction strategy. The rest of your data is unaffected.

The strategy pattern allows systematic upgrades. Each datapoint records which extraction strategy produced it:

datapoint.extraction_strategy = "employee_count_v2"

datapoint.extraction_model = "gpt-4-2024-01"

When you improve your extraction—better prompts, newer models, additional validation—you can reprocess selectively. Query for datapoints using outdated strategies, re-extract from the original sources (which you kept), and the new datapoints naturally supersede the old ones in reconciliation. No data deleted, full history preserved.

When you find out that "expert" you interviewed was full of shit, just flag them, and every fact attributed to them can be systematically downweighted. Their claims don't disappear (that would be data loss), but they stop corrupting reconciled values.

Confidence is explicit and configurable. Bad data doesn't corrupt the system; it gets outweighed. If three authoritative sources say "150 employees" and one sketchy source says "500," the reconciliation algorithm picks 150 and flags the outlier. You can tune source quality scores, adjust recency weights, set field-specific thresholds.

The key insight: trust in AI systems shouldn't be binary. It should be granular, transparent, and adjustable. We can't prevent LLMs from making mistakes. But we can build systems where mistakes are traceable, correctable, and contained.

When This Architecture Matters

This isn't the right approach for every AI project. Here's the quick test.

You DON'T need this if:

- You're building semantic search over documents (vector RAG works great)

- Hallucinations are tolerable and determinism isn't required

- You have a single source of truth with no conflicts to reconcile

- Users accept answers without asking where they came from

- You need to ship in weeks, not months

You NEED this if:

- Users need to query structured attributes with complete, precise results

- Wrong answers have real costs—millions lost, lawsuits filed

- Auditors will ask where a number came from (finance, healthcare, legal)

- Multiple sources conflict and you need systematic reconciliation

- You're blending public and private data with different visibility rules

If three or more of the "you need this" conditions apply, the upfront investment pays back every time a user asks "where did that number come from?" and you have an answer you can trust.

The pattern generalizes beyond PE diligence: healthcare records, legal filings, financial research, government databases. Any domain with entities, attributes, multiple sources, and consequences for errors.

Conclusion

The pattern we keep seeing: teams skip data architecture because AI feels like it should handle the mess. Embed everything, retrieve what seems relevant, let the LLM figure out structure at query time. It's seductive because schema design is hard, domain-specific work that requires thinking about your data before you have it.

This gets it exactly backwards. AI doesn't replace data architecture—it makes data architecture viable for domains that were previously too messy to model. Extraction, classification, normalization—tasks that used to require armies of annotators or custom ML pipelines—are now tractable at ingestion time. Queries become fast and cheap, but more importantly, answers become traceable and trustworthy.

AI at ingestion, structure for retrieval. We suspect this pattern applies far beyond PE diligence—anywhere you need exhaustive queries, audit trails, or deterministic results. The tools exist. The architectures are underexplored.

What we haven't figured out: how to handle schema evolution gracefully when your taxonomy changes mid-stream, and whether there's a smarter approach to entity canonicalization than "embeddings plus human review." If you've cracked either, we'd genuinely like to know.

If you've built something like this—or tried and hit walls we didn't mention—we'd love to compare notes.

About the Authors

Brian Bolze is a technical founder who previously co-founded Core (meditation hardware, acquired by Hyperice in 2021). At Doro, he led architecture and product, designing the datapoint pipeline and real-time query systems described here. BS/BA Duke (ECE/CS), MS Stanford (Management Science & Engineering). Based in Neptune Beach, FL.

Sarin Patel is a founding engineer who's been on three startup founding teams, including one acquired by Intel. At Core, he co-designed the biometric algorithms for real-time meditation feedback. At Doro, he built the extraction strategies and reconciliation engine that made production accuracy possible. MS USC (Engineering).

We're cleaning up a reference implementation—GitHub repo coming soon. Follow for updates.

Building something similar? We're happy to chat. Reach out on LinkedIn—in/brianbolze | in/sarinpatel—or Twitter @BrianBolze.